Habemus Verifier

March 30, 2024 by Thorkil Værge

Habemus Verifier

I heard you like verifying proofs, so I took your proof of verification and made a proof of its verification, so you can verify while you verify.

On March 18 2024, the first proof-verification program was executed in Triton VM.

Triton VM can, like any other virtual machine, take a program and an input and produce an output. What sets Triton VM apart is that it comes with a STARK engine. With a STARK engine you can generate a cryptographic proof that the resulting output comes from the input/program combination, and this proof can be verified without executing the program itself.

This means that a program/input/output combination can be verified much faster than it can be executed.1 It is computationally expensive to construct the proofs but generating a proof only needs to happen once, then the rest of the world can verify the output without having to rerun the computation.

"But wait!", I hear you say. "This sounds like a really useful technology for a blockchain. There you want it to be fast to verify the correctness of the state of the blockchain and you can accept that someone in the network, the miners, have to bear a heavy computational load."

On its face, it seems like verifying each block can be very fast, and that this would allow for the creation of a very nimble blockchain. A full-node could download all blocks and then verify the correctness of each block almost instantly.

But it turns out, we can do something much better.

Are you ready for this?

The program that verifies a proof can be run inside of Triton VM. Then we can generate a proof of the verification of another proof. We could output a new state and a proof that proves two things:

- That the new state and some further input follows from the old state

- That the proof associated with the old state is valid.

Then this new proof not only proves that the state was updated correctly but it also proves that the previous state was updated correctly. And the previous state had a proof that the one before it was also valid and so on. This way, the new proof proves that all previous state updates are correct.

One proof to rule them all, and in the STARKness bind them.

In blockchain terms this means that full-nodes only have to download and verify one block. Long synchronization times will soon be a relic of the past.

This is one of the goals of the Neptune blockchain.

Speeding it up

The time it takes to generate a proof of correct execution depends on how big the program is: How many times do you use the hash co-processor, the u32 co-processor, and how many clock cycles does it take to run the program? The biggest one of these numbers, scaled by some factors and rounded up to the nearest power of 2 is what determines how expensive it is to generate a proof. We call this value the "padded height". This will become important later.

Writing the verification program in a language Triton VM understands, Triton VM assembly (TASM), involved writing a lot of smaller code snippets2. Our first attempt relied heavily on compiler-generated code and had a clock cycle count of around 6m. Replacing a single function with hand-optimized assembler brought the clock cycle count down to a more reasonable 1.6m for a proof relating to the smallest possible TASM program.

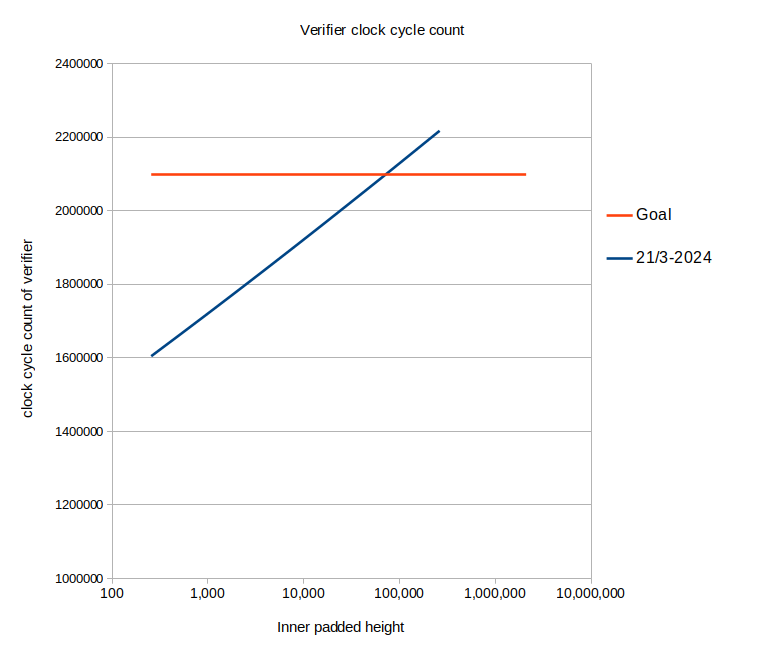

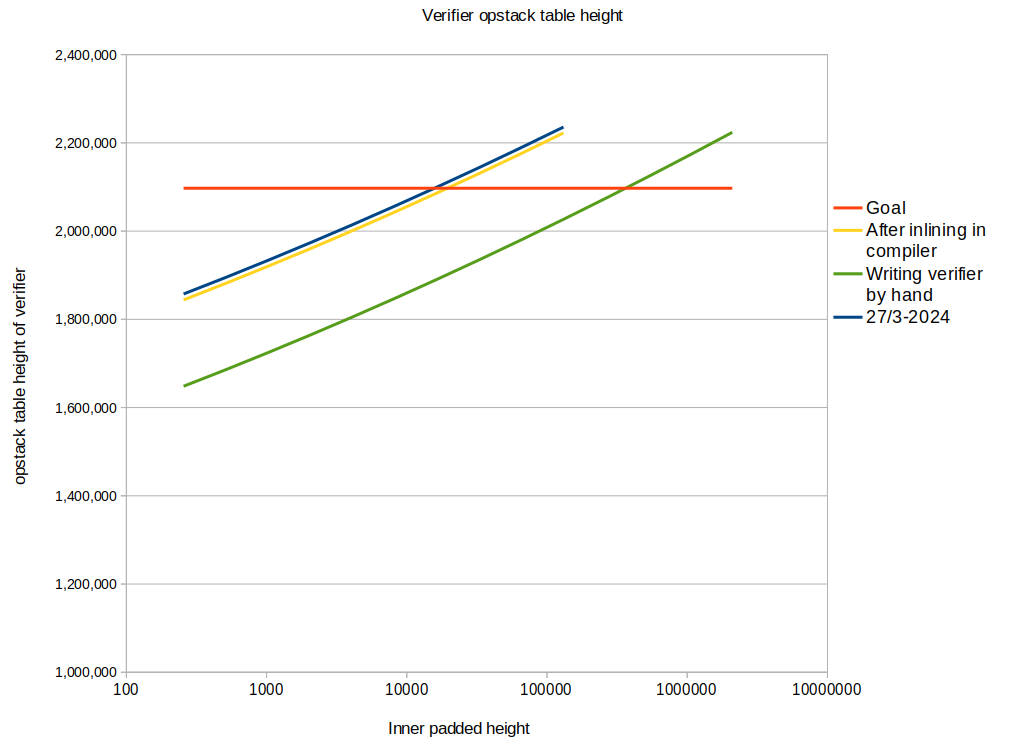

As a function of the "inner padded height" which is the program-size that the proof relates to, the clock cycle count is shown below. After introducing the above-mentioned hand-optimized code, we got to the blue line. And my immediate goal was to get below the orange line for an inner padded height of $2^{21}$ which would allow recursive proof generation to be handled on hardware in our possession, without having to use swap for extra RAM3. Assuming that clock cycle count is the dominating factor in the padded height, that is.

|

|---|

| Fig.1: Early status of the clock cycle count vs. inner padded height. |

There are many knobs you can turn to bring down the clock cycle count of the verifier, but some of them come with tradeoffs like bigger proofs, more RAM consumption in the prover, slower prover etc. An approach that doesn't have any tradeoffs but is a pure win is to hand-optimize the code, so I thought I would spend a few days trying to get reach the goal just by writing more efficient TASM.

|

|---|

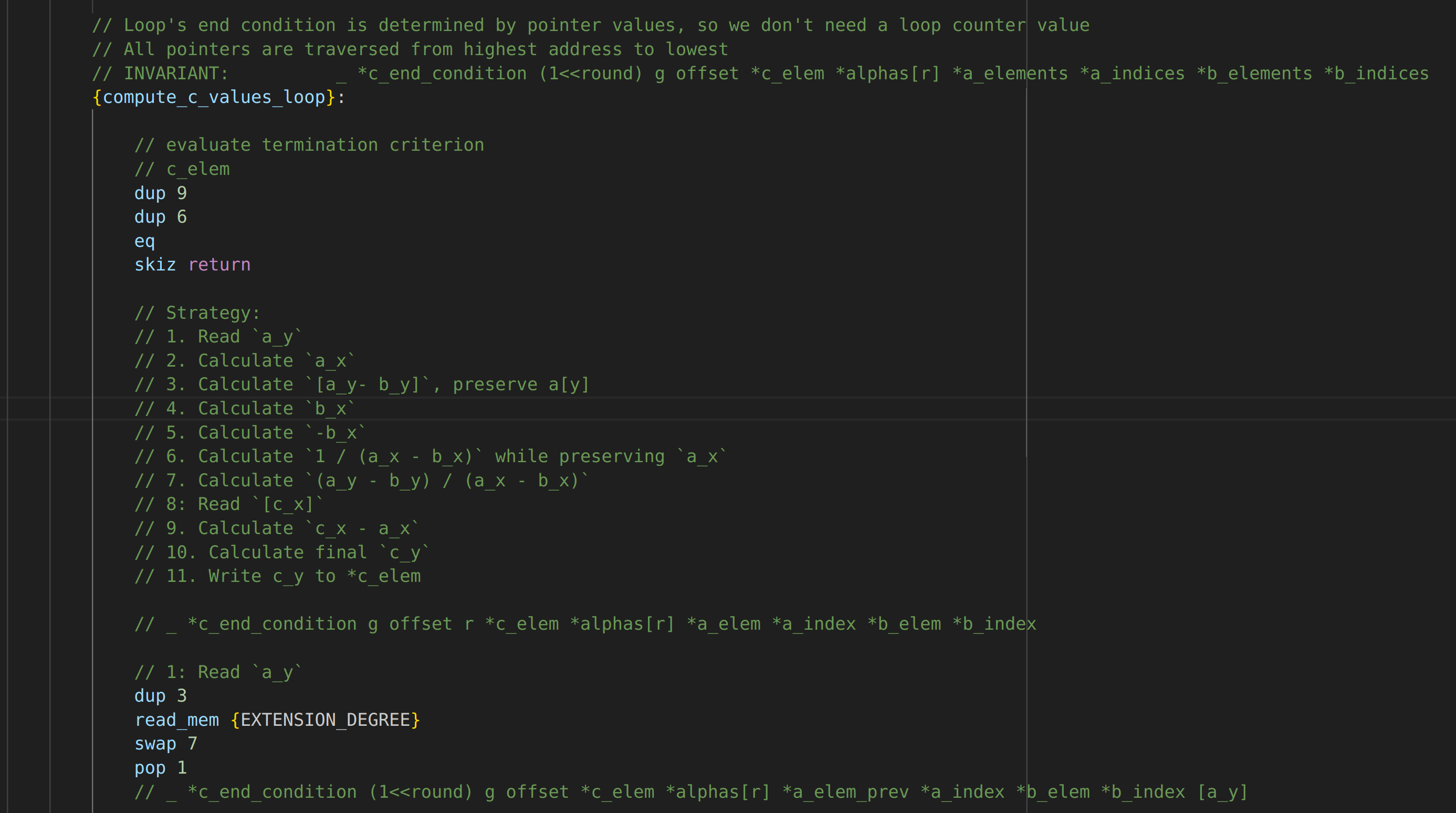

| Fig.2: Triton VM assembly code from the inner loop of the FRI verifier. This is my life now. Triton VM's instruction set can be found here. |

My first target was the higher-order function map which is used extensively in the verifier. By

switching from index arithmetic to pointer arithmetic, we gained around 60.000 clock cycles towards

our goal. Then zip was optimized to generate a similar speedup. And finally the inner-most loop

in FRI, a central component of the verifier, was optimized by inlining two function calls,

pre-calculating some values outside of the loop, and reducing the number of swaps which re-arrange

words on the stack. The efforts on FRI finally got us across the finish-line. I spent two-three

days just looking at the assembler of the FRI verifier, so this was a very nice reward4.

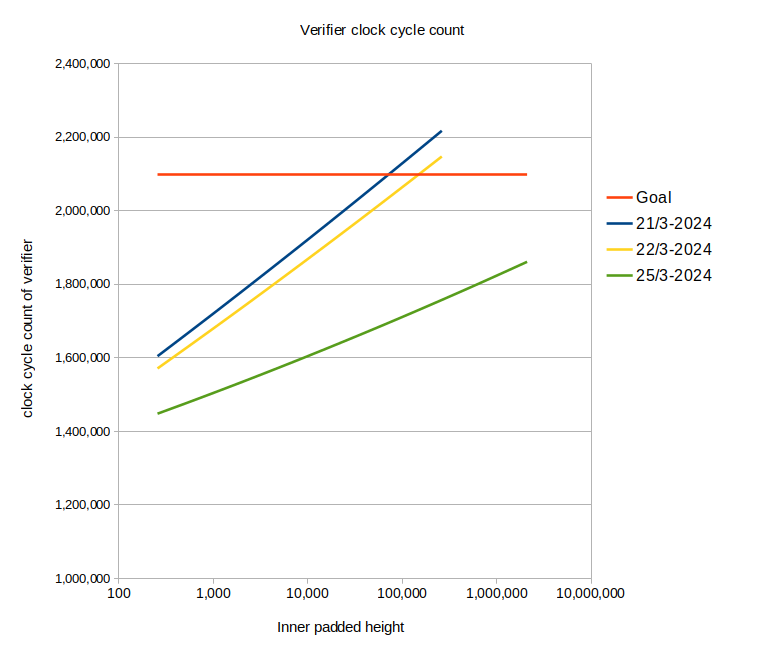

|

|---|

| Fig.3: Big improvements in the clock cycle count, mainly due to optimizations in the FRI verifier. |

Barking up the wrong tree

Except, it wasn't, or rather: Turns out I was measuring the wrong thing.

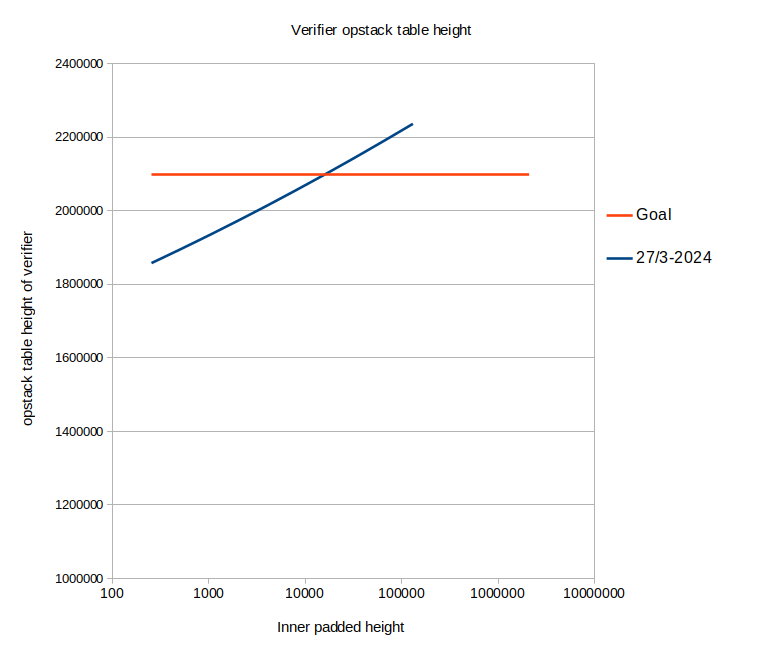

When I ran the prover on the verification of a proof that was itself the verification of a proof, the padded height was still $2^{22}$ and not $2^{21}$ as the goal was in this round of optimization. Remember how the padded height is determined by the biggest number from one of multiple co-processors? Turns out the clock-cycle count was not the bottleneck.

Instead the current bottleneck is the "opstack table". You can think of the opstack table like a co-processor similar to the hash co-processor or the u32 co-processor. It's the part of the prover that ensures that stack elements deep down in the stack, 16 elements and deeper below the top of the stack, do not change between each clock cycle5.

This opstack table gets an extra row each time the height of the stack changes. So it contains the total number of words with which the stack has changed its height.

As long as the opstack table dominates the padded height, swap instructions are free from the

point of view of the prover. Removing swap instructions from the verifier is basically what I spent

the last three days doing...

|

|---|

| Fig.4: Measuring the relevant numbers is important! |

A way forward towards $2^{21}$

So far we have only been benchmarking clock cycle count, the u32 table, and hash table, not the opstack table. Introducing a benchmark of the opstack table will help us identify which snippets constitute the bottleneck in terms of opstack table height. It's also possible that the goal can be reached simply by writing the entire STARK verifier directly in TASM instead of compiling Rust to TASM as we're currently doing.

Several knobs are at our disposal to bring the padded height down and the prover speed up:

- Unrolling loops so Triton VM does not have to count how many times a loop body has been executed

- Changing the proof parameters, specifically increasing a value called the FRI expansion factor. This should roughly halve the padded height of the verifier each time the expansion factor is multiplied by 4 but it comes at the price of a slower prover for the same program size.

- Changing how instructions work. Maybe the loop-related instructions could function without increasing or decreasing the stack height. This would shorten both the clock cycle count and the opstack table.

- Plain-old assembler optimization to remove unneeded copying of stack elements. Perhaps we can

replace some

dupinstructions, which grow the stack, withswapinstructions, which do not grow the stack? - Writing more snippets by hand and not relying on the compiler.

- Adding optimization steps to the compiler.

This might sound like bad news, but I see it as just another challenge and another reason to keep optimizing the assembler code, which is something I enjoy. Only by gaining a deep understanding of the relevant algorithms we want to run in Triton VM, verification being the most important, can one have a qualified opinion about which instructions to add or to change in Triton VM to speed things up. This is one of the benefits of building your own virtual machine: you have the entire design space at your disposal.

Update on Writing the verifier by hand

So I went about and wrote the entire verifier by hand. This involved writing only a few new snippets by hand and then a debug process that lasted a day where the I was using one of the snippets incorrectly. The last bug was found by simultaneously running the compiled verifier (that worked) and the hand-written verifier that didn't work yet in the excellent debugger written by Triton VM's lead engineer Ferdinand Sauer. That enabled me to find the discrepancy between the two versions6.

Here's the final result:

|

|---|

| Fig.5: Still not under the threshold, but a max table height that's 200.000 less than the compiled verifier. |

Verifying such a proof has a $O(log(N)^2)$ as opposed to a $N$ time of re-executing the program to verify its output. $N$ is the number of clock cycles it takes to execute the program.

The standard library that we've developed for Triton VM can be found here.

The prover used ~400GB RAM for a padded height of $2^{21}$, and ~800GB RAM for a padded height of $2^{22}$. There are ways to significantly bring down both the memory consumption and the padded height though, so expect both the padded height and the RAM consumption to drop by a factor of 4 or so. At the time of publishing, the RAM consumption has already more than halved from those 800GB to less than 400, so beware that prover will become significantly faster and cheaper to run during the next few months.

The commits reducing the clock cycle count of the verifier are listed below here. I have no excuse for my poor git discipline:

- Speeding up

mapby replacing index arithmetic with pointer arithmetic: https://github.com/TritonVM/tasm-lib/commit/c12fbaa4a97cfc891324e88193737783c58b1036 - Speeding up

zipby making it less general: https://github.com/TritonVM/tasm-lib/commit/4e81477f66afc02afb83326c9493eb26d74f1b8a - Speeding up the inner-loop of FRI: Multiple commits, the last one being: https://github.com/TritonVM/tasm-lib/commit/edab3a0a1bf3642078cfc4a386feb69632fd21c4

Ferdinand Sauer, the lead engineer on Triton VM, does a better job than me explaining how the prover works. He has a video on the subject, and a blogpost that goes into details about the tables in question. And Triton VM also has its own website.

The hand-written verifier can be found here.