Neptune Tokenomics

June 26, 2022 by Alan Szepieniec

Neptune Tokenomics

The token economics (tokenomics) of Neptune are similar to those of Bitcoin, but there are some important differences. This note clarifies them.

Asymptotical Limit of the Token Supply

Neptune coins come into existence whenever a block is found. How many Neptune coins are rewarded to the miner depends on the epoch. Initially the block reward is set to 128 tokens. Roughly every three years, a new epoch starts and the block reward is halved. As a result, there is an asymptotical limit of the token supply. This limit is 42 million, meaning that no more than 42 million Neptune coins will ever exist.

The difficulty is automatically adjusted to target an expected block time of 9.811832303157685 minutes, or 588.7099381894611 seconds. A new epoch starts every 160814 blocks, corresponding to roughly 3 years.

| Neptune | Bitcoin | |

|---|---|---|

| max. supply | 42 000 000 | 21 000 000 |

| block time | 9.8 min | 10 min |

| blocks per epoch | 160 814 | 210 000 |

| epoch duration | 3 years | 4 years |

These parameters define a money supply evolution similar to that of Bitcoin. Specifically, the slope halves in every epoch.

Premine

In order to reach 42 million tokens in the limit, the token supply needs to start at 831 600. These tokens are created by the genesis block, and distributed to the investors who provided the funds needed to develop Neptune. This premine is 1.98% of the asymptotical limit of the token supply.

Of course, the distribution depicted by the pie chart will only be reached in the limit. A more informative visualization is given by the evolution of the fraction of the token supply that was premined as a function of time. The next graph provides this image.

Stock-to-Flow

The stock-to-flow model has garnered a lot of attention as a plausible explanation as to why Bitcoin's bull-bear cycles seem to happen in sync with the halving schedule. It doubles as a metric for the hardness of a commodity, measuring roughly the inverse of the supply inflation rate.

Specifically, the stock-to-flow ratio is defined as the number of years it takes for the current issuance schedule to generate an amount equal to the total current supply. If it takes seven years to double the supply without changes to the issuance schedule, then the stock-to-flow ratio is seven. In graphical form, it pays to take the natural logarithm of the stock-to-flow ratio; this gives rise to the familiar staircase pattern.

According to this extrapolation, Neptune's stock-to-flow ratio will overtake that of Bitcoin by 2068. Of course, there is more to hard money than the relation between new and existing supply

No Tail Emission

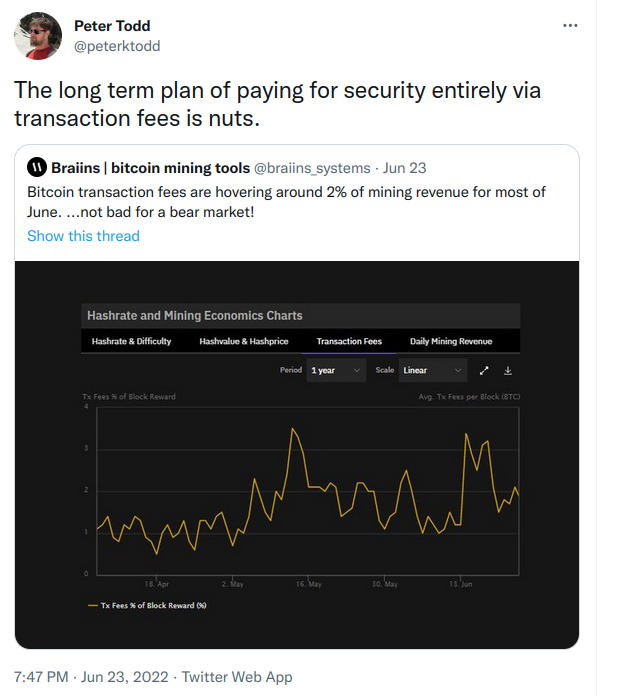

Some cryptocurrencies feature a tail emission, which is a nonzero lower bound on the issuance rate. It guarantees that there will always be a block reward, even if the transaction fees do not reward the miner for his energy expenditure. Some bitcoiners also avocate for this policy.

The argument goes something like this:

- A cryptocurrency security against reorganization comes from the incentive for miners, which is proportional to the value of the fees and block reward.

- In the long run, the cryptocurrencies with tail emission allocate a larger proportion of the token supply to miners, compared to cryptocurrencies without.

- Ceteris paribus, the incentive for miners to mine is greater for cryptocurrencies with tail emission than for cryptocurrencies without.

- Therefore, cryptocurrencies with tail emission offer more security against reorganization in the long run.

The problem with this argument is the ceteris paribus. One cannot make a change to the issuance schedule and simultaneously assume that this change has no effect on the token's value.

A tail emission policy means that there is no asymptotical limit on the token supply. Whatever slice of the pie a person owns will necessarily shrink over time. A medium with this property will store value less effectively than a medium with a hard limit. Capital that is sensitive to the effect of this depreciation will move to the medium that preserves wealth better, and the price will reflect this movement.

That is not to say that all capital will necessarily move to the harder money. Hypothetically, it might be the case that the cryptocurrency with tail emission offers a faster growth of the difficulty of reorganization (the invalidity of the above argument notwithstanding). This state of affairs exposes a distinction regarding the sensitivity of capital to urgency of transactions. Persons wanting to prioritize spendability may choose to pay the price of a depreciating currency. Conversely, persons wanting to minimize the evaporation of their capital, for instance across large anticipated stretches of time, may pay for this priority by having to wait longer for their transactions to be confirmed to the same degree.

Under the alternative hypothesis, namely that the harder money also has the better evolution of reorganization difficulty, the harder money is also more amenable to making transactions that confirm fast. The fees will be larger, but the net effect of larger fees is to prioritize larger transactions where the fee is a smaller relative cost. Smaller transactions will find a home either on Lightning, or otherwise on blockchains for which there is less demand.

In both cases, Neptune's zero tail emission policy is more conducive to storing large amounts of wealth across large spans of time.